The importance of humanising an African sound archive

By Atiyyah Khan

The question of African sound archives remains a mystery on the continent. This comes down to a lack of access, which in turn has led to a huge knowledge gap. For those of us seeking knowledge, narrowing this gap has become a very important purpose.

In my own sound practice as a music journalist, DJ, archivist and record collector living in South Africa, this is a never ending process of learning and what can best be described as digging – constantly finding clues that leads us deeper into a process. From a DJ perspective, the word ‘crate-digging’ refers to searching through endless crates of dusty records in order to find the rarest one. However in my own case currently, this is almost always focused on looking for African sound archives.

In my earlier days, while working first as a music journalist, it was clear that information relating to black music had been missing and it was really hard to find information on even recent history. The local libraries had music books only written by Europeans and very little research had been done by African scholars. In South Africa’s case, Apartheid was the reason for much of this – due to the continuous censorship and sonic control of black music.

It meant then, that another approach had to be found and the only way to truly learn about the past was through the process of oral histories.It then became a common practice for me to visit older musicians and try to document their stories as best as possible while they were still alive. Truly a daunting task with a heavy weight of responsibility!

Years later, as a DJ, the world of music opened up much more through the collecting, curating, listening and studying of records. Originally while my focus was on playing jazz and collecting all genres of music – it soon became clear that there was a higher purpose for me. I realised that very little was known about our own music, but also that of the rest of Africa – due to being kept separate from the rest of the continent for so long. It then became a mission to try and increase knowledge in any way possible, but through the very organic process of listening and studying.

The results were remarkable and revealed so much! Looking for African records revealed not only some of the best music I’ve ever heard – but it revealed so much about place, culture, politics, time, space, language and people. Going one step further, my research took me into what is considered ‘Library Records’ or ‘Field Recordings’ of ‘African Tribes’. These are all very contested and problematic words that put sophisticated Africans on display, as exotic objects. Nevertheless for the sake of education, I placed this as a focus of my own learning which continues today.

Where do these archives live

Historically, African music was not recorded in the Western sense as there was no need for this. African people preserved their sound through oral traditions carried through generations over centuries. It was not until the advent of Westerners reaching Africa, did the desire or need for documentation of these sounds arise. This is also the reason much of these studies still are steeped in obscurity and reserved for those who have access to universities and academic institutions. But I believe this knowledge should be for everyone, and it is truly our duty to make it accessible to all those within Africa, first and foremost.

Through the process of crate-digging, I would start coming across these old recordings which all had specific clues and common factors. It would for instance be the album of rare ethnic African sounds, recorded and translated by the white explorer or documentor or scholar, who took the initiative to press record and preserve this music. The cover art would almost always have an indigenous African person advertising the music. There are thousands and thousands of records like these, many of which have become incredibly expensive or impossible to find.

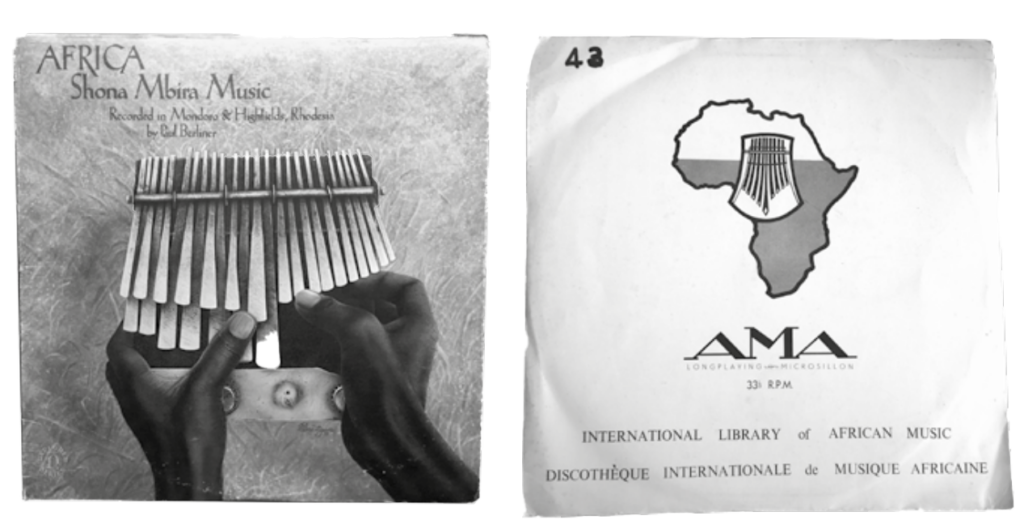

For example, one of the earliest recordings to reach my collection was the album “Africa: Shona Mbira Music – recorded in Mondoro and Highfields, Rhodesia’” by Paul Berliner in 1977. Berliner is an American ethnomusicologist who has worked extensively in African music archives. However, upon showing the album to a Shona artist, she confirmed that many of the interpretations of the stories and lyrics on the back of the record (written and displayed as factual for the listener), were mostly incorrect and incomplete. This is just one example of a common problem with many African archives – ie: The inability of Westerners to completely grasp the message behind the music because of their own shortcomings through language and cultural misunderstanding.

In close reach to me and one that had for a long time been of interest was the ILAM – or International Library of African Music. What the Smithsonian calls, “the greatest repository of African music in the world”, it is the collection of historian and sound archivist Hugh Tracey founded in 1954. The archive currently sits in the town of Makhanda (formerly Grahamstown) in the Eastern Cape, an isolated town – far out of reach from many in South Africa. The archive stretches back to 1929 and had also included a sound journal and the majority of the collection is focused on sub-Saharan African music.

I came to learn about Hugh Tracey through the lens of a sonic coloniser, or someone who took sounds from Africans – however the story is a bit more complex than that. For a time, I would collect any ILAM records I could find – but in July last year, I traveled to Makhanda and sought out and interviewed Andrew Tracey – the son of Hugh Tracey who had started the library. An in-depth interview revealed all the gray areas of the story. The younger Tracey spoke in great detail about the lengths his father would have to go to, in order to get to the most rural and remote areas to record these obscure and rare African musics from across the continent. He took me to the inner library of the centre and showed me the earliest recordings and also played some indigenous instruments from their collection, which have since become extinct.

One example of a record from ILAM for instance is, “Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola: Various Artists ILAMTR036A (1957)” described as: Chokwe songs and dances with various drums from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola . These dance songs, accompanied by goblet or conical drums, were recorded in mining compounds in the DRC and Angola, where the Chokwe had gone to work.

Another one is, “Songe topical songs – Various Artists: ILAMTR020 (1957).” Described as: Ngoi Nono, Kabongo Anastase, and several friends accompany their singing on two guitars, a struck bottle, and a rattle.They are Songe, from the Kabongo area of what is now southern DRC.

On the one hand, we can criticise many things about Hugh Tracey and his methods, but on the other hand we now have some recorded sounds to listen to and work from. Perhaps the greatest value of this archive is that it still remains on African soil.

I do not know of any other sound and music archives that exist in the rest of Africa, although I am certain they do exist. However the biggest problem faced right now for many of us, and returning back to the topic of access, is that – most of these recordings, artifacts and sound archives are sitting in various parts of the Western world.

One example is the Vienna Phonogrammarchiv in Austria – which is the first sound archive in the world and was founded in 1899 by members of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. The collection has over 67 000 recorded items. It preserves a large collection of audio and visual material in over 250 languages from Africa – with the earliest sound recordings of an African language dating back to 1905. There are also objects, photographs, films, handwritten and published documents, and books in the collection.

There are many others like these existing in the Western world – but they are not accessible to us. One would need to travel there and spend time listening to the archive, and we face visa and financial restrictions. They remain out of reach and the knowledge gap continues to grow. Even with the aid of some digitisation, most of these archives are only accessible to scholars or those in academia.

African sound archives must return back home and must exist first on African soil, before existing anywhere else in the world. In a similar way, so does all the invaluable art that was looted and stolen, now sitting in museums across the world, need to be given back.

The importance of digging

Since majority of these archives are sitting in libraries or universities outside of Africa, it is then important for us to continue to build an African archive of sound on home soil firstly, and then make that music accessible. There is no better platform than the practice of DJ-ing to make this music reachable to the people and this is what I have incorporated into my sets. Finding a way to fuse the past and present into a new way of listening.

Why does digging up African sound archives matter? For one, it narrows the gap of our missing history. It also allows us to correct the misrepresentation of the past through the colonial lens. It teaches us more about history, politics and culture. But also, it shows us how sound moved across borders and influenced each other in different regions. For instance, listening to ululations from southern Africa in relation to how they are heard in parts of northern Africa.

When examining music from Congo, we can also see how sound has moved beyond borders and become part of the national identity of other music, specifically through the guitar. Today, without digging back to those original roots, it is almost impossible to trace how certain music came to be and where it came from.

In today’s circumstances, we are still stuck with the sound hegemony of the West as being the originators of culture and music. From classical or high-art music, up to modern contemporary pop or dance floor sounds – the history of black music (through jazz, dub, rock ‘n roll or techno) has been almost erased from mainstream modern discussions and how these sounds came about.

This once again, reinforces to me the importance of continuing the work of digging for new knowledge in all its forms about African music and oral traditions. How to learn, listen, understand and then share – in order to process this for others and change the storyline through writing and journalism. By trying to understand and by listening, we aim to form compassion for the past, we try to right the wrongs and we offer a way of humanising those ancestors who came before us.

By Atiyyah Khan

Africa: Shona Mbira Music, 1977 (Photo by Atiyyah Khan)

Atiyyah Khan is an arts journalist, archivist, record collector and events curator from Johannesburg and based in Cape Town.

Since 2007, she has documented arts and culture and has been published in newspapers across South Africa. She was the 2010 Pulitzer Fellowship recipient for her masters studies at the University of Southern California.